Table of contents

Nothing on the internet is free | Glossary | What is a third-party cookie? | Timeline | Why are third-party cookies going away? | What will replace third-party cookies? | Who gets to decide what will replace third-party cookies? | What will the outcome of all this be?

Nothing on the internet is free

From news articles to web comics to cat videos, the internet has more media than you could ask for, much of it available for you to access without paying a dime.

But nothing in life is free, and the internet is no exception. In reality, there’s a deal happening every time you consume a piece of free content online. Web publishers are giving you their content; advertisers agree to fund that content by paying for ads. And you agree to give mountains of personal data to hundreds of companies in the digital ad industry, whether you realize it or not.

That’s the bargain that has funded free web publishing since the mid-1990s, and for the past quarter century it’s been powered by a key piece of technology known as third-party cookies. These are tiny but crucial identifiers that track internet users’ every move across the web. They help advertisers target ads and measure the effectiveness of their marketing campaigns. They’ve become one of the central technologies underpinning the business model of publishing on the web.

And they’re about to die.

Safari and Firefox, the world’s second and third most popular web browsers, already block third-party cookies by default to protect users’ privacy. Google Chrome—which controls two-thirds of the global browser market—has announced it will follow suit by 2022. When Google pulls the plug next year, almost no one will be left using a browser that supports third-party cookie tracking, rendering it effectively extinct.

The death of third-party cookies comes at a moment of widespread backlash against advertisers’ digital surveillance. The public has become increasingly vocal about its discomfort with ad tracking. Europe’s landmark digital privacy laws have spawned copycats all over the world. Apple, sensing an opportunity to market itself as the privacy-friendly tech giant, has announced software updates that will make it much harder for advertisers to track what users do in apps and mobile browsers.

The internet is now at an inflection point. Industry groups representing advertisers, advertising agencies, browsers, and publishers are scrambling to come up with alternatives to the old methods of invasive personal tracking. The decisions they reach over the next year will have widespread implications for the future of privacy on the web and how the businesses that operate on the internet carve up the spoils of the $336 billion industry of digital advertising.

It’s hard to overstate what hangs in the balance. “If we do it right,” said Chetna Bindra, who heads Google’s product team on trust and privacy, “this will be the way to proactively shape the next couple of decades for a free and open web.”

Glossary

Publishers: Companies that create and host content online, including news organizations and independent creators.

The “open” web: The universe of content that is free for anyone to access using a web browser—no one has to log in or pay a fee to see it.

Walled gardens: In this story, this term mostly refers to companies that collect data on their websites that they won’t share with anyone (e.g. Facebook, which has vast troves of data on its users that no one else can see). But in other contexts, it can mean publishers that require users to log in or pay a fee to access content (e.g. Quartz, which requires you to become a member to read this story).

Brands: The companies that buy ads to market their products or services. The biggest advertisers in the world include brands like Procter & Gamble, Samsung, and L’Oreal.

Agencies: The firms that brands hire to design and execute their marketing campaigns.

Adtech: A catchall term for the hundreds of companies that help connect brands, which have ads they want to place, with publishers, who have ad space they want to sell. Adtech companies automate the process of buying and selling ad space, track web users to help companies target the audiences they want to reach, and measure how effectively a marketing campaign is getting people to spend money with a brand. Google is one of the world’s largest adtech companies, but the group also includes smaller, independent firms like The Trade Desk, LiveRamp, Criteo, and ComScore.

Programmatic advertising: Ads bought through automated exchanges enabled by the adtech industry. There is no direct relationship between the brand and the publisher. Publishers sell space to the highest bidder, and brands place ads targeted to particular audiences, regardless of the publisher who hosts them. This accounts for a large portion of digital ad spending—85% in the US in 2020.

First-party data: The data internet users give directly to a company. If you go to a brand’s or publisher’s website, everything you do and all the information you enter counts as first-party data. For publishers, that might include what kinds of articles you like to read; for brands, that might include what kinds of products you like to buy.

Third-party data: The data a company gets indirectly, either by tracking you or buying it from someone else. There are companies that base their entire business on buying and selling data on internet users’ demographics, location, income, and browsing history.

What is a third-party cookie?

A cookie is a small text file saved locally on a user’s computer at the behest of a website they’ve visited. It helps the website remember information about them—usually for benign reasons, like remembering their login information or making sure the items in their shopping cart will still be there even if they close the page and come back later. Up until recently, websites saved cookies on visitors’ computers automatically, without ever notifying them. (In response to European privacy laws, many websites now have pop-ups informing visitors that they use cookies.)

When cookies come directly from a website a user chose to visit, they’re called first-party cookies. For example, if a user goes to a weather website and types in their zip code to get their local forecast, the site might save a cookie on their device. That way, it will remember a user’s location—and offer the right forecast more quickly—the next time they visit.

When cookies come from someplace other than the website a user chose to visit, they’re called third-party cookies. For example, if a user goes to a website that displays an ad, that ad might save a cookie on their computer that reports back to the advertiser. The cookie then marks them as the person who saw this particular ad at this particular moment. If at some point later they visit the advertiser’s website and buy something, the company can infer that its marketing campaign influenced their decision and was effective.

The digital ad industry has learned many ways to use third-party cookies to its advantage. Ever notice that, when you click on a product listing for a pair of pants, ads for that particular pair of pants begin following you everywhere you go online? It may be because the retailer saved a cookie on your computer identifying you as a potential pants buyer. Ad vendors can also use cookies to keep track of the websites you’ve visited, and link that information to massive third-party datasets on consumer incomes, demographics, or addresses. In this way, a beauty brand might target ads for its products only to affluent women who live in geographic areas where the company operates.

Advertisers began adopting third-party cookie tracking around the turn of the millennium because targeted ads promised to solve two of the industry’s perennial problems. First, they offered a simpler way to reach the right audience at scale. Before cookies, a brand might painstakingly cut deals with individual magazines, TV channels, or websites based on their inferences about how likely it was that Golf Digest readers would be in the market for a new watch. Now, brands can just say they want to reach wealthy, middle-aged men who have browsed fashion websites in the past month, and cookie trackers will attempt to find those men anywhere they happen to be around the internet.

“We became a little bit dependent on third-party cookies because it was easier, faster, and required less planning and integration [than traditional marketing],” said Matt Naeger, who heads US strategy for the performance marketing agency Merkle.

Cookies also promised to bring some scientific rigor to the advertising process. Agencies could analyze cookie data and calculate how much revenue a particular marketing campaign generated. In fact, an entire sub-industry dedicated to “performance marketing” now promises its clients clear returns on their investment based on rock-solid data. The allure of these precise figures stands in contrast to the traditional ad model, in which brands simply have faith that their investments in marketing would eventually bring in customers.

In reality, however, third-party cookies haven’t turned out to be the omniscient crystal balls they promised to be. Even before ad blockers (which also block tracking cookies), consumers had a pesky habit of clearing their cookie caches and sharing a browser with other members of their household, leaving the data noisy and incomplete. To further muddy the waters, the internet is awash in bots designed to fabricate ad traffic to generate billions of dollars in fraudulent revenue for nefarious publishers and adtech vendors. Today, cookies are rather lousy proxies for a consumer’s identity. When one adtech vendor tries to match the cookie data it has on a given audience to another vendor’s cookie data on those same people, the accuracy rate tends to hover between 40% and 60%—a major challenge for advertisers who want to track individuals around the web.

Peer-reviewed academic research has struggled to find evidence that cookie-based tracking actually makes advertising more effective, according to Arslan Aziz, an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia business school who wrote the 2016 paper “What Is a Digital Cookie Worth?” His study found that, under the right circumstances, ads that use cookie tracking could make a person 2.7% more likely to make a purchase than ads that don’t. But he said other studies have been more equivocal. “Frankly, the research is not conclusive about whether these ads do add value,” he said.

Adtech firms, however, have been very successful at convincing brands that tracking is worth the investment. “We know from basically just looking at the industry that advertisers do spend a lot of money on [ad targeting] and that translates into revenues for all these big tech firms that work on advertising and all these other players in the ecosystem,” Aziz said. “So there is a lot of money being spent. Now whether it creates a lot of value, but it’s difficult to measure, or it doesn’t create any value, I feel it’s still not fully answered in research.”

Timeline

1994: Lou Montulli, a 23-year-old engineer at the world’s then-leading web browser, Netscape, invents the cookie. His original goal was to create a tool that would help websites remember users—but couldn’t be used for cross-site tracking.

1995: DoubleClick, one of the world’s first adtech firms, is founded. Its engineers realize they can exploit cookies to track users across the web; the company pioneers and comes to dominate the world of ad targeting.

1996: The press starts reporting on cookie tracking in advertising, prompting public backlash. At Netscape, the decision about whether to ban third-party cookies falls to Montulli, who decides to spare them. Netscape, however, gives users full power to clear their cookie cache or delete cookies from specific websites, which other browsers later emulate.

1998: The US Department of Energy Computer Incident Advisory Capability issues a bulletin assuring the web-browsing public that “the vulnerability of systems to damage or snooping by using Web browser cookies is essentially nonexistent.”

2008: Google buys DoubleClick for $3.1 billion and expands its advertising business from search pages to programmatic ads on websites.

2011: The European Union issues an ePrivacy Directive enshrining individuals’ right to refuse cookies.

2016: The EU passes the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which expands requirements for websites to get users’ consent before tracking them with cookies.

Sept. 2017: Safari starts blocking some third-party cookies through the first iteration of its Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) protocol.

April 2018: Citing GDPR, Google blocks adtech companies from accessing DoubleClick data, strengthening its grip on a walled garden of user data.

Oct. 2018: Firefox rolls out “Enhanced Tracking Protection” features that block third-party cookies, but these are switched off by default.

Aug. 2019: Google Chrome announces its “Privacy Sandbox” initiative to develop and test new browser features that would boost user privacy.

Sept. 2019: Firefox blocks all third-party cookies by default.

Jan. 2020: Google announces it will block all third-party cookies by default, writing, “Our intention is to do this within two years.”

March 2020: Safari blocks all third-party cookies by default.

Why are third-party cookies going away?

The immediate cause of death for third-party cookies was Google Chrome’s decision to stop supporting them. But Google’s decision was really a recognition of the reality that cookie-based tracking had suffered a swift and irreversible fall from grace. At this point, there are few people left in the ad industry willing to defend—or invest in—third-party cookie tracking.

First, public opinion turned negative. A major catalyst for change was Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal—which, ironically, had nothing to do with cookies. But after the news broke in 2018 that a third-party analytics company had improperly accessed Facebook users’ data in an attempt to psychologically manipulate voters and sway elections, the media cast a harsh spotlight on the ways tech companies harvest and exploit data. Public awareness of and opposition to tracking grew. On top of that, a steady drumbeat of headlines about massive data breaches undermined the public’s faith that the companies that collect data could be trusted to protect it.

When laying out its justification for nixing third-party cookies, Google cited public opinion polling from Pew Research Center showing that 72% of Americans worry that almost all of what they do online is being tracked by advertisers, tech firms, and other companies; 81% believe the risks they face from having their data collected outweigh the benefits. Pew has also found that half of Americans have chosen not to use a product or service (mainly websites, electronics, and social media platforms) because they worried about how much personal data it would collect about them.

Souring public opinion spurred regulation. Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation law passed in 2016, and quickly became the template for similar privacy regulations around the world. The new rules restricted the use of cookie tracking by requiring companies to obtain opt-in consent from users before saving cookies on their computers. The laws also convinced companies that more regulation could be on the horizon, and it was a good time to take some proactive steps to preserve privacy and appease lawmakers.

Apple sought to claim a competitive advantage by positioning itself as a privacy-first consumer tech company. Safari, which has blocked some forms of third-party cookies since 2017, completely banned them in 2020. Apple has also said it will release a software update in “early spring” 2021 that will require advertisers to ask for permission before tracking iOS users’ activity on mobile devices. The update is expected to limit the industry’s use of Apple’s “Identifier for Advertisers,” which plays a similar role to cookies on mobile devices.

Apple’s privacy moves were inspired by Firefox’s 2019 decision to block all third-party cookies by default, and coincided with the rise of ad blockers, third-party extensions that allow users to swat down tracking cookies even on browsers like Chrome. Thanks to Firefox, Safari, and ad blockers, roughly 40% of US web traffic now comes from users who block third-party cookies, reducing cookies’ utility to advertisers.

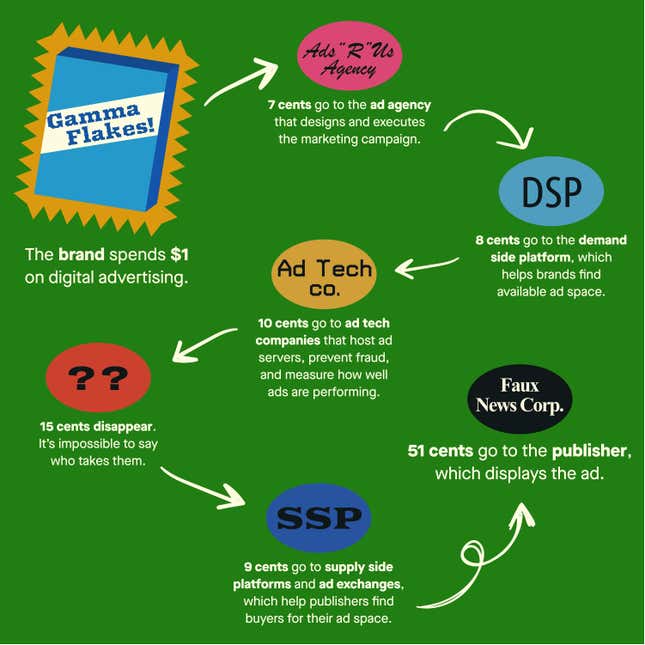

As public backlash, regulatory scrutiny, and competitive pressure rose, advertisers started to take a closer look at the adtech business model that third-party cookies were propping up. Advertisers’ reliance on tracking data had created an elaborate industry of hundreds of adtech firms, each using third-party cookies to facilitate a niche part of the process of buying and selling digital ads. A 2018 analysis from the Incorporated Society of British Advertisers (ISBA) found that agencies and adtech middlemen—who connect brands buying ads to publishers selling ad space—absorbed roughly half the revenue from programmatic advertising (confirming earlier findings from the World Federation of Advertisers and the US Association of National Advertisers).

Worse, the digital ad industry was so opaque that almost none of the advertisers the ISBA reached out to could fully audit their spending. In the industry group’s analysis, 15% of ad spending seemed to simply disappear. No one could account for where it went or who pocketed it.

Against this backdrop, Google announced in Jan. 2020 that it would stop supporting third-party cookies within two years. Initially, industry groups like the US Association of National Advertisers and the American Association of Advertising Agencies grumbled in press releases that they were “disappointed that Google would unilaterally declare such a major change” and worried that the move would “threaten to substantially disrupt much of the infrastructure of today’s Internet.”

But they quickly fell in line and embraced the change. In roughly 30 recent interviews with representatives from brands, agencies, adtech firms, publishers, privacy watchdogs, and academia, not one person mourned the third-party cookie. Stephan Pretorius, chief technology officer at UK-based WPP, the world’s biggest ad agency, gave a representative response: “I’m not particularly sad about the demise of third-party cookies because they were never really that accurate, never really that useful, and in fact I think this whole thing has helped us all to rethink what data matters,” he said.

What will replace third-party cookies?

There are three major proposals for how the industry can continue to show consumers relevant ads and measure the effectiveness of marketing campaigns without relying on third-party cookies. Google is championing a browser-based tracking model; publishers and brands are developing ad models that rely on their own first-party data; and some parts of the adtech industry are pushing for a new form of identity-based tracking that would bear some similarities to the cookies of yore.

These solutions aren’t mutually exclusive, and at least in the short term, we’ll see the industry experiment with all three.

Google’s browser-based model

How it works: The browser would collect information about what a user does online and save that data locally on their computer. Based on the websites they visited and the content they saw, the browser would assign them to a cohort alongside several thousand people with similar interests. Then, every time that person visits a website, their browser would tell the site which cohort they belong to, and advertisers would show them ads tailored to people with interests like theirs. The cohorts would update every week, to keep ad targeting relevant and make it harder to identify the members of each group.

Who’s working on it: Google Chrome is currently testing a version of this, which it calls the Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC) model. Chrome engineers are hammering out the details of how it should work with representatives from ad agencies, publishers, and adtech firms who meet regularly as part of a working group at the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), an industry group that sets technical standards for web browsers. No other browser has publicly indicated it is working on a similar model.

Stage of development: In beta testing. Google says that 0.5% of users in Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, the Philippines, and the United States are part of its initial “origin trial.” (Europe was not included, for fear that the trial might violate GDPR.) If you’re a Chrome user in one of those countries, you can check if you’re part of the trial.

How it improves privacy: FLoC has two privacy-preserving features. First, all tracking data is saved locally on a user’s computer—it never gets collected in a central server, and it can’t be resold to third parties. Second, advertisers never see specific information about an individual user; they only see aggregated information about a group of thousands of users in the same cohort.

Caveat: FLoC wouldn’t change the fact that Chrome users’ every move online is being logged and tracked—it would just make it harder to tie that data back to an individual. (But, as the privacy-focused Electronic Frontier Foundation points out, that doesn’t stop advertisers from trying to de-anonymize consumers through a practice called “fingerprinting,” which some adtech companies already use to track people.)

How it would affect the ad industry: In this model, all tracking, targeting, and measurement runs through the browser. No one else has access to the underlying data, giving the browser a tremendous amount of control over the digital ad market.

Who wins: Google. The company can legitimately claim it boosted user privacy while also consolidating its grip on web advertising.

Who loses: Adtech vendors, especially those who run independent ad exchanges or rely on granular, individual-level user tracking.

First-party data tracking

How it works: Publishers collect their own first-party data about their audience, which might include information about the content they’re viewing, the kinds of topics they tend to be interested in, and possibly survey responses about their interests and demographics. They can use this data to divide their audience into segments, and sell ad space to advertisers who want to target those segments. Meanwhile, brands also collect their own first-party data about their customers’ shopping habits. If a brand and a publisher have the same piece of information about a particular user—say, they both know their email address or phone number—they can team up to match the customer’s spending habits on the brand’s site to their reading habits on the publisher’s site and target ads even more effectively. Note that these kinds of partnerships require direct deals between brands and publishers, who have to set up complicated technical systems that make the ad targeting work without revealing brand’s data to the publisher or the publisher’s data to the brand.

Who’s working on it: Large-scale publishers like the New York Times, Vox Media, and Insider have already launched their own ad targeting systems based on first-party data. The Local Media Consortium is working on a massive partnership between 5,000 US-based local news outlets to build a first-party data system that would sell ad space across all their websites, in an effort to match the scale of the big publishers. (Quartz, which makes money from both ads and memberships, has its own first-party data strategy.)

Stage of development: Several large publishers are already using them, while the Local Media Consortium is beginning to pilot its proposed ad network.

How it improves privacy: Instead of being tracked by third parties they don’t know, consumers give their data directly to publishers and brands. Ideally, this creates a clear “value exchange” in which consumers knowingly and voluntarily give up their data in exchange for free content, discounts, or other incentives.

Caveats: Consumers may not be fully aware of when their data is being collected and what happens with it afterward. When someone gives a publisher their email address and agrees to receive marketing emails in exchange for free articles, the terms of the deal are obvious. But it’s less clear that consumers are thinking about handing over data for advertising every time they make a purchase or log into a website. Plus, companies can make deals with third-party data vendors to “enrich” the first-party data they get from consumers—a process that allows them to match the users in their first-party database with information the third-party vendor has about their homes, their cars, their incomes, their demographics, their credit histories, and so on, for ad targeting purposes. (Vice has struck a partnership along these lines with credit agency Experian.) Consumers, in other words, may be giving away access to a lot more information than they realize.

How it would affect the ad industry: First-party data comes with fewer headaches around complying with privacy regulations and managing user consent. But first-party data is also much harder to get than third-party cookie data. Under this model, the ad world would have to learn how to make do with less information about consumers.

Who wins: The biggest publishers with access to the largest pools of first-party data could wind up making more money under this model by cutting direct ad deals with brands. Also, brands that have access to lots of consumer data, e.g. direct-to-consumer brands, would gain a marketing advantage over brands that have no direct relationships with consumers.

Who loses: Smaller publishers who don’t have as much first-party data and lack the scale they’d need to secure ad deals with major brands. Also, brands that haven’t invested in collecting consumer data through direct-to-consumer sales, subscriptions, loyalty programs, newsletters, etc.

Identity-based tracking

How it works: A central authority would assign every web user an advertising ID based on a trait that isn’t likely to change very often, like their email address. Every time a user logs into a website with their email address, advertisers could identify and track them using their specific ID. Adtech companies would once again be able to monitor individual users’ browsing habits, serve them targeted ads, and measure whether a user who saw an ad went on to buy the advertised product. If enough of the ad industry agreed to use this form of ID tracking, and more websites started requiring users to log in with an email address, the digital ad world could return to a system for targeting ads that would look something like the cookie-based system we have today.

Who’s working on it: The Trade Desk, one of the web’s leading adtech companies, has developed the most prominent proposal, which it calls Unified ID 2.0. It has gotten buy-in from a slew of adtech companies and industry groups like the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Tech Lab and the Partnership for Responsible Addressable Media (PRAM), which are developing technical standards for identity-based tracking.

Stage of development: In beta testing.

How it improves privacy: User IDs would be encrypted, so advertisers wouldn’t see a person’s email address—they’d just see a random string of characters that correspond to that email address. The IAB Tech Lab has also proposed creating a “Global Privacy Platform” which would help the companies that use Unified ID 2.0 offer consumers a way to opt out of ad tracking. It wouldn’t create a universal opt-out button, however—consumers would still have to opt out of tracking from each company individually.

Caveats: In reality, people just don’t use opt-out menus. It’s not clear how many consumers would know the opt-outs existed or go to the trouble of finding them and fidgeting with their privacy options.

How it would affect the ad industry: The ad industry wouldn’t have to change their business practices very much after third-party cookies fade away, maintaining the status quo. Advertisers wouldn’t be able to collect as much data as they did with cookies, but the data would be more reliable because it would come from logged-in users. But critics worry this solution wouldn’t sufficiently address consumers’ or regulators’ privacy concerns, and would leave the industry open to a renewed backlash.

Who wins: Adtech vendors whose business models depend on granular tracking, and who worry about the market power of Google and Facebook. Smaller publishers who rely heavily on programmatic advertising and don’t want to have yet another business model change foisted upon them.

Who loses: Potentially the digital ad industry, if fed up consumers and regulators believe this solution doesn’t go far enough and they turn their ire on advertisers.

The other alternative would be for the industry to move away from tracking and back toward old-school marketing methods. Instead of targeting ads to individual users, brands could return to contextual advertising, in which they place ads in publications or next to stories with relevant content. Instead of following users around the web to see if they eventually buy a product after seeing it in an ad, marketers could rely on last-click attribution—an imperfect way of measuring an ad’s effectiveness by simply observing how many people click on it and whether those clicks lead to sales. Both tactics can be imprecise, but they don’t require cookies or any cookie alternatives.

In other words, the industry could let go of its preoccupation with measuring everything, and operate the way it did before the internet: with a lot less data, and a lot more faith that good marketing will eventually carry the day. Naeger, the Merkle ad executive, said the industry has lost sight of the basics of building a brand and maintaining relationships with customers. “The first job you have is to be a real marketer,” he said. “The second job you have is to take advantage of the tools and technologies that allow you to do it in a faster and easier way.”

Who gets to decide what will replace third-party cookies?

There are hundreds of players in the digital ad world who all have a hand in deciding which cookie alternatives the industry will adopt. But three main power centers have emerged with outsized influence over the future of tracking on the web.

Google is working on standards for browser-based tracking through the W3C’s Improving Web Advertising Business Group. The 355-member group is, theoretically, supposed to be collaborative and make decisions based on consensus among all its stakeholders, who represent browsers, ad agencies, adtech firms, and publishers. But it’s hard to find common ground with so many competing interests at the table.

“It’s hard to point to something that everyone agrees on,” said Wendy Seltzer, the W3C’s legal counsel, strategy lead, and chair of the advertising working group. “When I’ve tried to suggest points of agreement even around the basics—we’re trying to work on solutions that improve privacy and opportunities for monetization—I get pushback from some group participants.”

Absent any consensus, it’s unlikely the group will come up with standards for browser-based tracking by 2022. That frees up Google—which never needed the W3C’s permission in the first place—to forge ahead with its own vision for FLoC. Jochen Schlosser, the chief technology officer at the adtech company Adform and a participant in the W3C working group, says the meetings have started to feel like a Google-led show-and-tell.

“It’s not a conversation,” he said. “It’s not about trying to be creative together or trying to find a compromise. This is about someone doing a show and then taking feedback, and then saying, ‘Thank you for listening. It was great having you.’” Schlosser has stopped attending the meetings, and instead sends someone in his place to take notes on Google’s latest updates.

Bindra, the Google privacy lead, says Google remains committed to collaborating with its peers on the W3C. She points out that Chrome’s latest prototype—a tool for replacing digital ad auctions that it calls FLEDGE—incorporates some of the extensive feedback the company got from the working group. But the end product does bear a lot of similarities to Google’s original proposal.

Large publishers

The largest web publishers aren’t convening industry groups to develop shared standards to govern their first-party ad targeting software. Many saw the writing on the wall when GDPR passed in 2016 and started developing their own ad platforms soon after.

So far it seems to have been working—at least for publishers with the largest audiences. Jana Meron, who leads Insider’s programmatic advertising and data strategy, says the publisher has been able to keep significantly more of its ad revenue by signing direct deals with brands based on first-party data. Schlosser, the Adform CTO, says that a “double digit percentage” of traffic on his company’s ad network now comes from publishers who use first-party data for ad targeting. “We’ve had no complaints about their performance, so I think that proves first-party solutions are already working,” he said.

The Trade Desk & the IAB Tech Lab

Despite pushback from some parts of the industry, The Trade Desk is moving ahead with Unified ID 2.0. The IAB Tech Lab is in talks to take on the role of overseeing the tracking system, and has put out a set of standards for how Unified ID 2.0 should be governed. Industry groups including the Partnership for Responsible Addressable Media and the American Association of Advertising Agencies have tentatively expressed an interest in the new tracking protocol.

The big, remaining hurdle is getting the rest of the ad world onboard. The more brands, agencies, adtech firms, and publishers use Unified ID 2.0, the more comprehensive its ability to track users across the web will become—and, in theory, the more useful it will be to advertisers. But some players worry that adopting a new form of identity-based tracking will just set off another wave of public outcry over privacy.

In March 2021, Google threw up a roadblock for Unified ID 2.0 when it declared that it would not support identity-based tracking in its ad products. “We don’t believe these solutions will meet rising consumer expectations for privacy, nor will they stand up to rapidly evolving regulatory restrictions, and therefore aren’t a sustainable long term investment,” the company wrote in a blog post.

Some publishers have echoed the sentiment. Megan Walton, who heads Vox Media’s ad tech team, said identity-based tracking is ineffective and short-sighted. “We don’t think that’s the future out of how advertising will be transacted and we think that’s not the correct strategy,” she said. Pranay Prabhat, who heads digital ad technology at The New York Times, agreed. “I don’t think that’s the future,” he said.

Still, there are a couple of major publishers who have shown support for Unified ID 2.0. The Washington Post became the first publisher to agree to test the tracking system for ad targeting on its site, and The Trade Desk lists Buzzfeed and Newsweek as collaborators on the project.

What will the outcome of all this be?

No matter how the battle to select third-party cookies’ replacement shakes out, we can expect two major outcomes: modest privacy gains for users and increased consolidation in the digital ad market.

Consolidation

The clearest beneficiaries from the death of third-party cookies are the web’s walled gardens, especially Google and Facebook, who have vast pools of data about users and their browsing habits that no one else can access. There’s also room for Amazon to become the third ad industry titan, since it controls its own walled garden full of rich data on consumer spending habits. Over the past several years, the ecommerce giant has been steadily growing its ad marketplace, which now accounts for 10.3% of the US digital advertising.

Adtech vendors, on the other hand, are shut out of all this information. When third-party cookie tracking goes away, they won’t have their own walled gardens full of data to fall back on. Many of their business models, which rely on collecting and analyzing vast troves of user data, won’t work anymore. Larger adtech vendors will be able to pivot to new supporting roles in an industry that relies more on FLoC cohorts and highly technical first-party data partnerships—but smaller adtech firms may struggle to keep the lights on as they try to find a new niche.

The same is true for publishers. Bigger publishers may be able to boost their revenues by charging more for ads that use first-party data to target their large audiences. But smaller publishers are less likely to have the developers on staff who can build out a first-party data offering, the sales people who can knock on brands’ doors to offer direct ad deals, or the scale that would make it worth it for a brand to cut deals with them individually.

It’s possible that small publishers can band together in partnerships like the NewsNext program envisioned by the Local Media Consortium to pool resources and build their own ad offering based on first-party data. Otherwise, they’ll have to hope that cookie alternatives like FLoC and Unified ID 2.0 continue delivering programmatic ad revenue after third-party cookies get phased out. If not, they’ll have to find ways to make up for lost income, such as boosting subscription rates.

At least marginally better privacy

Any of the proposed alternatives will offer more privacy protections than the status quo, in which hundreds of adtech companies surreptitiously used third-party cookies to collect mountains of data about users without their knowledge or consent. But it’s unclear whether the cookie alternatives will offer anything more than a small step in the right direction.

FLoC promises to hide users’ identities in large, anonymous groups, but advertisers could use fingerprinting to de-anonymize FLoC cohorts. Unified ID 2.0 promises to come with opt-out buttons, but few people actually take advantage of opt-outs. First-party data promises to be the gold standard, in which users knowingly and voluntarily give their data directly to a publisher or brand in exchange for content, a discount, or something else they value. But consumers may not fully understand the implications of giving away their data.

The biggest privacy gain to come out of the industry’s switch to cookie alternatives may be the disruptions that it causes. Whatever comes next will likely throw a wrench in what used to be a relatively smooth data collecting operation—which ran quietly enough in the background that most users didn’t have to think about the fact that it was happening. The transition may require companies to ask users for their consent to give up their data more often. It may require users to click through more obtrusive privacy pop-ups. It will probably create more friction, at least in the short term, in the experience of using the internet.

But that friction will create awareness. It will force users to more frequently face the fact that they are being tracked by advertisers. And it will force advertisers to be a little more transparent about why they’re asking users to hand over their data. The industry believes it’s ready for that moment of honesty—and that it has a convincing sales pitch that can win over consumers.

“The internet is this amazing offering, where you have essentially unlimited content—news, entertainment, political views, social networking sites—available to consumers that never before have existed, and all of it is mostly free. And that is powered by advertising,” said Travis Clinger, vice president for addressiblity at the adtech firm LiveRamp.

If you explain that to people, Clinger and many of his peers believe, they’ll get why companies need to target ads to them to fund web publishing. They’ll be willing to barter their data for the bounty of the internet. It’s just that no one has ever clearly laid out the terms of the deal to them. “The third-party cookies didn’t really transparently explain the value exchange, and I think that’s on adtech,” Clinger said. “We did a bad job of telling that story to consumers.”

Consumers will not escape tracking as a result of the ongoing changes in the digital ad industry. This is, after all, an attempt at self-regulation from an industry that has convinced itself, rightly or wrongly, that it needs extensive user data to generate value—so there’s no way it will create a new system that doesn’t give advertisers access to plenty of user data. Changing that fundamental reality would require government intervention.

But the industry may, at least, become a little more transparent about the terms of the deal it’s striking with consumers. And consumers, in turn, may be a little better equipped to make decisions about when to trade their data away.